If you’ve been following PostgreSQL development for the last few years, you’ve probably heard the term commitfest manager a few times. You probably already know what a commitfest is, but why is there a manager? Since I spent a good deal of time this past January managing one, I’ll explain.

Patch applied during commitfest

At its heart, a PostgreSQL commitfest is just a collection of patches awaiting integration into the PostgreSQL code base. A commitfest’s working principle is that each patch that has been sent to pgsql-hackers must be reviewed timely; once reviewed and revised enough times, the patch is candidate for permanent inclusion into PostgreSQL by a committer.

As for the commitfest workflow: each new patch starts life in the commitfest in “needs review” state; it can be closed as “rejected” (breaking the author’s fragile heart), “committed” (making the author’s day, or week, or month), or “returned with feedback” (whereby the author needs to keep at it, knowing what to do to improve the patch, and resurrect it in a future commitfest). There’s a short-lived status also, “waiting on author”, which is used for quick feedback expected to result in a new version of the patch in a few days again as “needs review”. As long as we have some things marked “committed” and authors get good feedback, things are moving along: PostgreSQL grows, evolves and matures to become the next “major release”.

So far so good.

Why do we need a manager?

The attentive reader may have noticed that there are three groups of people involved in the process: patch authors, reviewers, committers. There is a lot of overlap among those three groups, which is where the problems begin. To do a good code-level reviews, people need to understand the code, and those that do are also writing patches of their own. On the other hand, committers are just reviewers which are supposed to have better abilities at finding and fixing code “issues”. Committers are also writing their own patches all the time.

The problem is that if a patch author continues to work on their own patches exclusively, they will not have time to review or commit other people’s patches. This can happen easily if they receive feedback and immediately work on another version resulting in more feedback; this creates a loop that can go on for very long. At some point, the fair thing to do is for the author to drop the patch from the commitfest and work on reviewing somebody else’s patch; but because everyone believes their patches to be very important, this seldom happens spontaneously.

That’s where the commitfest manager enters the picture. One task is to garner interest from pgsql-hackers people into actually reviewing patches. Most of the time, sending public emails to the group is enough to get people reading, discussing, testing, thinking about patches. Often, patch authors need to be reminded that they need to look at other people’s patches, not just their own. The commitfest application has a handy send-an-email interface which can be used for that. These things are normally sufficient to create a good amount of cross-review.

There’s an old, almost forgotten rule: if a patch author doesn’t do reviews, their patches can be closed from the commitfest without further consideration. To my knowledge, this has never happened, which goes to state that at least to some extent patch authors are being “good citizens”.

Thus, be it by persuasion or coercion, a commitfest manager can get people to review patches, which mostly wouldn’t occur spontaneously except when hackers are already working in cooperation.

On the other hand, patch authors sometimes leave their patches to linger without updates. One possible answer is to simply close them “returned with feedback”, but most of the time it is worth nudging an author into submitting an updated version.

The commitfest manager can also spend a good deal of time doing reviews of their own, and if they have commit privileges, committing patches.

Finally, it’s the commitfest manager’s responsibility to ensure all patches are closed when the commitfest is over, which normally should be one month after it started. For patches that have received feedback, to which the author has responded with another version, it is fair to “move the patch to the next commitfest”: the commitfest’s promise (to give feedback) has been kept. However, doing that to patches that have not received any feedback is unfair. Closing commitfests becomes more difficult when that happens.

The January 2016 commitfest

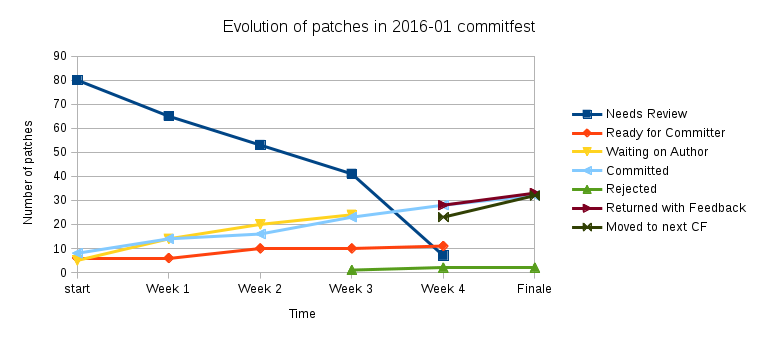

This chart illustrates the January 2016 commitfest. The data is from the weekly status emails I sent: start, week 1, week 2, week 3, week 4, finale.

You can see that we started out with 85 in “needs review” or “ready for committer” status, meaning they were waiting on somebody other than the author to act. One week later we were down to 71 patches on those statuses: that means 14 patches were processed in one week, which is not bad because, if sustained, that rate meant that the whole patch queue would be over in just 5 more weeks.

However, during that first week I committed six trivial patches. Those run out pretty quickly, and the rate of commit is expected to decrease. Fortunately, other committers were hard at work, and you can see that the rate of committed patches was pretty much constant for the whole period. It’s probably possible to achieve this in all commitfests, assuming appropriate persuasion is applied to committers.

It’s visible that the “returned with feedback” status only appeared at the end of the commitfest. It pretty much continues the trend seen in the “waiting on author” line. In my opinion, this is okay. Some people would prefer certain patches to be “booted” early on, so that efforts are focused on the patches that really have a chance of getting in (a “triage”, if you will). I’m not sure about that myself, so I didn’t apply that idea here.

I think this commitfest was moderately successful in getting patches committed; the progress in that front was certainly visible, if not necessarily enormous. I also think it was hugely successful in ensuring that every patch author got some fair amount of discussion of their patches. So, for my part, I’m satisfied with the job done.

Advice to future commitfest managers

I think that having weekly status updates gives good results: it gives everyone the impression that something is happening (which it is), motivating both reviewers and committers into doing their jobs.

Also, I took the approach of listing a few patches needing attention each time — not the same patches every time, but rather I focused on a different set each time, to make sure every stalled patch got a kick somewhere. This is subtle work: it would be easier to just list all patches needing attention, but if you do that, eyes glaze over gigantic lists and everything continues to be ignored.

Any opinions you have regarding how the commitfest was managed would be appreciated; please email me if you don’t want to post it publicly as a comment. If you think things I did were ineffective, or if you have other ideas on what to do, I’m willing to listen. I may manage other commitfests in the future, resources permitting.

Finally, prepare yourself for the upcoming March 2016 commitfest. It’s going to be the final commitfest for 9.6 and I’m sure there will be plenty to do for everyone. Happy patch reviewing!